Jack Colreavy

- Nov 28, 2023

- 5 min read

ABSI - Targets Out & Tenders In to Achieve Renewable Energy Goals

Every Tuesday afternoon we publish a collection of topics and give our expert opinion about the Equity Markets.

Later this week the 28th UN Climate Change Conference, otherwise known as COP28, will kick off in Dubai for two weeks. During this time, government representatives from around the world will analyse progress on climate goals and discuss new policies to help economies achieve the Paris Accords of Net Zero by 2050. For Australia, the event will expose their global peers to the progress of their carbon reduction plans, in particular the carbon reduction and renewable energy targets of 43% and 82% by 2030 respectively. In fear that they’re falling behind on these targets, the Australian government made an incredibly important shift in energy policy last week. ABSI will explain this policy change.

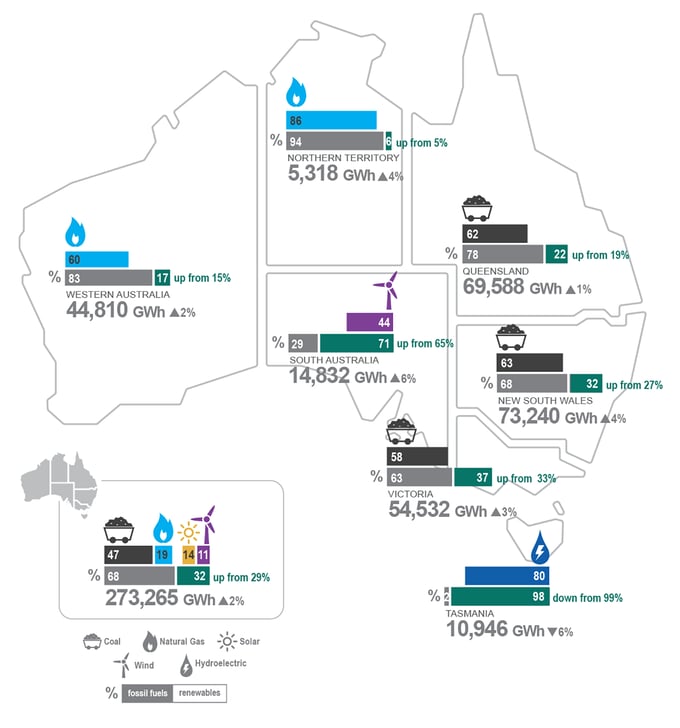

In 2022, Australia legislated carbon emission reduction targets committing to a 43% reduction on 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050. Part of the 2030 goal is for renewables to contribute to 82% of the nation’s energy requirements. This target is ambitious as the grid is still dominated by fossil fuels, with a 68% contribution in 2022, of which 43% is coal. Eight years from the 2030 finish line and renewables only contribute 32% of our energy needs. Moreover, with the growing electrification trend, our energy demand is only going to increase over the decades ahead.

Electricity Generation by Fuel Type

Source: Energy.gov.au

The official Albanese government contingent will set off for Dubai later this week for COP28, and they will need to be armed with evidence that their emission reduction targets are on track or risk being vilified by their international counterparts. Enter climate change minister Chris Bowen, who last week announced one of Australia’s biggest changes in energy policy by taking a more hands-on approach. Targets are out and tenders are in with contracts-for-difference (CFD) being the financial mechanism of choice to supercharge the growth in renewable energy investment needed to achieve emission reduction targets.

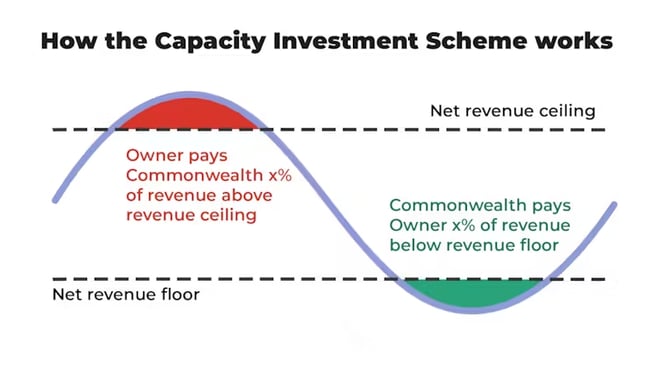

For the uninitiated, a CFD is a contract between a buyer and a seller, where the difference between the pre-specified prices of the contract is settled in cash. Importantly, participants are not buying or selling an actual asset but rather agreeing to exchange the difference in the asset's value from the time the contract is opened to when it is closed. How this enables renewable energy investment in Australia is the government will create a floor price of electricity, safeguarding downside pricing risk for market participants. For example, a tender is conducted whereby a wind farm developer bids a strike price for a CFD with the government. Once the project is up and running, the wind farm will be connected to the National Electricity Market (NEM) and be exposed to the spot price, determined by the supply and demand of electricity. If the average spot price received by the wind farm is a specified percentage (say 5%) below the CFD strike price, the government will provide the wind farm with a payment to bring the revenue up to the agreed strike price. However, the CFD works both ways, if the spot price is 5% above the CFD strike price, then the wind farm will have to hand over those excess gains to the government.

Source: The Conversation

This reboot to the renewable energy target has a goal of underwriting new projects that will deliver 23GW of renewable energy and 9GW of dispatchable capacity (i.e. batteries). The first auction is set for April 2024 and will repeat every 6 months till 2027. Total investment for this new capacity is estimated to be at least A$40 billion and proponents are praising the approach as a cost-effective means to achieve climate goals. This is based on the view that, in an ideal world, the government won’t have to spend a cent on the new infrastructure.

On the other hand, while there are no upfront costs to the government, critics point to the underwriting risk that has been burdened by the government, and therefore Australian taxpayers. If the projects consistently breach the price floor then the government is on the hook for billions in CFD payments to the energy developers into the future.

Personally, I think the policy is an effective one, provided that the auction price levels are reasonable. The risk of material payments being made are low given the increasing demand for electricity and the amount of coal-fired generation due to exit the grid over the next decade. The biggest price risk will be to the solar projects, given that NEM prices are regularly negative in some states during peak solar radiance. There also isn’t much announced to address transmission infrastructure bottlenecks which remain the biggest barrier for new renewable energy projects to come online.

We offer value-rich content to our BPC community of subscribers. If you're interested in the stock market, you will enjoy our exclusive mailing lists focused on all aspects of the market.

To receive our exclusive E-Newsletter, subscribe to 'As Barclay Sees It' now.

Share Link